These views are my views personally, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Weather Service as a whole.

After one of the greatest tornado outbreaks in history, it is crucial to reflect back on what went right, what went wrong, and figure out how we can improve. The National Weather Service will do a thorough service assessment. Although it is too early to say anything conclusive about the NWS's performance in this outbreak, here are some of my thoughts in general (keeping in mind that I work in Alaska, and am not totally up to speed on NWS short-fuse thunderstorm warning services).

We need to focus more on social science, and less on meteorology. The weather conditions that lead to tornados or severe thunderstorms are no secret. Sure, there's room for improvement in meteorological research, such as understanding what exactly makes a regular mesocyclone evolve into an actual tornado. However, all this research is meaningless if the public does not take appropriate actions when severe storms/tornadoes are imminent.

One of the most concerning things to me is that people generally seek confirmation of a threat before taking action. For example, when a tornado warning is issued, people will generally call their friends, turn on the TV, check twitter or facebook, look out the window, or even wait to hear a tornado siren to confirm the threat. This diminishes the effectiveness of the warning and high lead time. In the recent outbreak, many people received this confirmation by watching TV. In particular, the Tuscaloosa/Birmingham tornado was broadcast live by local media. This was an "ideal" scenario: people got blatant confirmation of the threat and were more likely to seek shelter. This underlies the importance of the NWS having a strong relationship with local media, who generally have a better capability to relay the message and inspire people to take actions.

However, what if this "confirmation of the threat" cannot be obtained? Will people take action? This is where analysis of NWS products and services is important. One of the more notable changes in recent years is the addition of "tornado emergency" verbiage, distinguishing the most urgent scenarios from "tornado warnings". While in certain situations "tornado emergency" can inspire people to take actions, this is not ideal, as it diminishes the importance of tornado warnings. Tornado warnings these days are generally issued for any decent mesocyclone in a storm, which often does not translate to a tornado. Radars are only useful to an extent in detecting if a tornado is on the ground because beams ascend with height as you get further away from a radar. Obviously, having tornado warnings for every mesocyclone can lead to complacency and "warning burnout" for the public, and they may not take appropriate action when the threat is really high. I don't have a great solution for this problem. I do believe that it is valuable for the public to know when there is rotation in a thunderstorm that could produce a tornado. However, in the marginal situations, I would argue that the threat from the thunderstorm itself (hail/straight-line winds/flooding) is just as high as the threat for a small tornado. How can we solve this? Maybe tone down the number of tornado warnings to the high end cases. And, in severe thunderstorms which have a mesocyclone which could produce a tornado, word it as such: "severe thunderstorm warning with a possible tornado", and make two polygons, one being an embedded polygon which will trigger the "possible tornado" wording. Any other ideas?

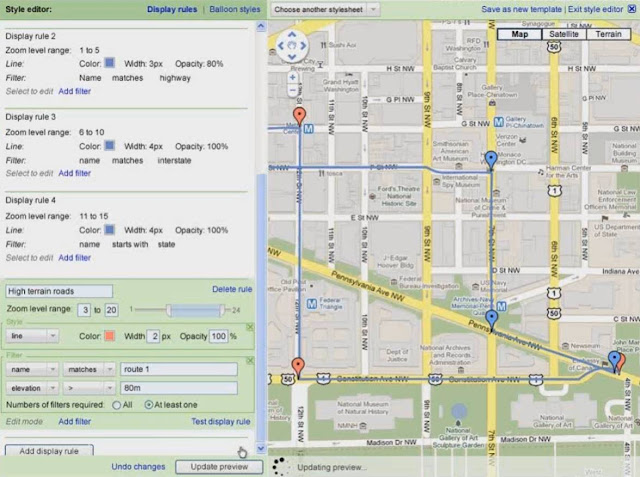

One other significant problem is that NWS "pathcasts/polygons" are not fully integrated into warning systems. Much larger areas are warned through siren activation/weather radio/etc than need to be. NWS polygons for tornado warnings are fairly precise. If only the people who are physically in these polygons were warned, this would cut down greatly on what the public perceives as false alarms. The technology is out there to accomplish this, but unfortunately is takes money. Here's an idea that I'm sure is being looked into. Many people carry around GPS-enabled smart phones, and this number will only increase, as will coverage. How about a text message alert if the person's smart phone is physically within the polygon? This would be something built into smart phones (ie little configuration required for the user), where the highest end alerts, such as tornado warnings and civil emergency messages, will appear on the smart phone if the phone is within the polygon.

Any other ideas out there on how to improve warning services and inspire people to take appropriate action? Or is there not a problem at all?